CORE BRANCHES

Philosophical questions can be grouped into several branches. These groupings allow philosophers to focus on a set of similar topics and interact with other thinkers who are interested in the same questions. Epistemology, ethics, logic, and metaphysics are sometimes listed as the main branches.[92] There are many other subfields besides them and the different divisions are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. For example, political philosophy, ethics, and aesthetics are sometimes linked under the general heading of value theory as they investigate normative or evaluative aspects.[93] Furthermore, philosophical inquiry sometimes overlaps with other disciplines in the natural and social sciences, religion, and mathematics.[94]

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies knowledge. It is also known as theory of knowledge and aims to understand what knowledge is, how it arises, what its limits are, and what value it has. It further examines the nature of truth, belief, justification, and rationality.[95] Some of the questions addressed by epistemologists include "By what method(s) can one acquire knowledge?"; "How is truth established?"; and "Can we prove causal relations?"[96]

Epistemology is primarily interested in declarative knowledge or knowledge of facts, like knowing that Princess Diana died in 1997. But it also investigates practical knowledge, such as knowing how to ride a bicycle, and knowledge by acquaintance, for example, knowing a celebrity personally.[97]

Analysis of Knowledge

One area in epistemology is the analysis of knowledge. It assumes that declarative knowledge is a combination of different parts and attempts to identify what those parts are. An influential theory in this area claims that knowledge has three components: it is a belief that is justified and true. This theory is controversial and the difficulties associated with it are known as the Gettier problem.[98] Alternative views state that knowledge requires additional components, like the absence of luck; different components, like the manifestation of cognitive virtues instead of justification; or they deny that knowledge can be analyzed in terms of other phenomena.[99]

How People Acquire Knowledge.

Another area in epistemology asks how people acquire knowledge. Often-discussed sources of knowledge are perception, introspection, memory, inference, and testimony.[100] According to empiricists, all knowledge is based on some form of experience. Rationalists reject this view and hold that some forms of knowledge, like innate knowledge, are not acquired through experience.[101] The regress problem is a common issue in relation to the sources of knowledge and the justification they offer. It is based on the idea that beliefs require some kind of reason or evidence to be justified. The problem is that the source of justification may itself be in need of another source of justification. This leads to an infinite regress or circular reasoning. Foundationalists avoid this conclusion by arguing that some sources can provide justification without requiring justification themselves.[102] Another solution is presented by coherentists, who state that a belief is justified if it coheres with other beliefs of the person.[103]

Many discussions in epistemology touch on the topic of philosophical skepticism, which raises doubts about some or all claims to knowledge. These doubts are often based on the idea that knowledge requires absolute certainty and that humans are unable to acquire it.[104]

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, studies what constitutes right conduct. It is also concerned with the moral evaluation of character traits and institutions. It explores what the standards of morality are and how to live a good life.[106] Philosophical ethics addresses such basic questions as "Are moral obligations relative?"; "Which has priority: well-being or obligation?"; and "What gives life meaning?"[107]

Main Branches of Ethics

The main branches of ethics are meta-ethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics.[108] Meta-ethics asks abstract questions about the nature and sources of morality. It analyzes the meaning of ethical concepts, like right action and obligation. It also investigates whether ethical theories can be true in an absolute sense and how to acquire knowledge of them.[109] Normative ethics encompasses general theories of how to distinguish between right and wrong conduct. It helps guide moral decisions by examining what moral obligations and rights people have. Applied ethics studies the consequences of the general theories developed by normative ethics in specific situations, for example, in the workplace or for medical treatments.[110]

Contemporary Normative Ethics

Within contemporary normative ethics, consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics are influential schools of thought.[111] Consequentialists judge actions based on their consequences. One such view is utilitarianism, which argues that actions should increase overall happiness while minimizing suffering. Deontologists judge actions based on whether they follow moral duties, such as abstaining from lying or killing. According to them, what matters is that actions are in tune with those duties and not what consequences they have. Virtue theorists judge actions based on how the moral character of the agent is expressed. According to this view, actions should conform to what an ideally virtuous agent would do by manifesting virtues like generosity and honesty.[112]

Logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It aims to understand how to distinguish good from bad arguments.[113] It is usually divided into formal and informal logic. Formal logic uses artificial languages with a precise symbolic representation to investigate arguments. In its search for exact criteria, it examines the structure of arguments to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Informal logic uses non-formal criteria and standards to assess the correctness of arguments. It relies on additional factors such as content and context.[114]

Deductive Arguments

Logic examines a variety of arguments. Deductive arguments are mainly studied by formal logic. An argument is deductively valid if the truth of its premises ensures the truth of its conclusion. Deductively valid arguments follow a rule of inference, like modus ponens, which has the following logical form: "p; if p then q; therefore q". An example is the argument "today is Sunday; if today is Sunday then I don't have to go to work today; therefore I don't have to go to work today".[115]

Non-Deductive Arguments

The premises of non-deductive arguments also support their conclusion, although this support does not guarantee that the conclusion is true.[116] One form is inductive reasoning. It starts from a set of individual cases and uses generalization to arrive at a universal law governing all cases. An example is the inference that "all ravens are black" based on observations of many individual black ravens.[117] Another form is abductive reasoning. It starts from an observation and concludes that the best explanation of this observation must be true. This happens, for example, when a doctor diagnoses a disease based on the observed symptoms.[118]

Incorrect Forms of Reasoning

Logic also investigates incorrect forms of reasoning. They are called fallacies and are divided into formal and informal fallacies based on whether the source of the error lies only in the form of the argument or also in its content and context.[119]

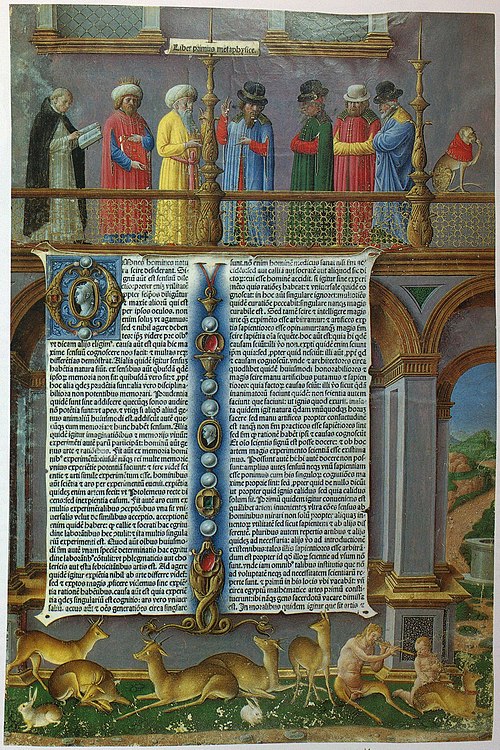

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the study of the most general features of reality, such as existence, objects and their properties, wholes and their parts, space and time, events, and causation.[120] There are disagreements about the precise definition of the term and its meaning has changed throughout the ages.[121] Metaphysicians attempt to answer basic questions including "Why is there something rather than nothing?"; "Of what does reality ultimately consist?"; and "Are humans free?"[122]

Metaphysics is sometimes divided into general metaphysics and specific or special metaphysics. General metaphysics investigates being as such. It examines the features that all entities have in common. Specific metaphysics is interested in different kinds of being, the features they have, and how they differ from one another.[123]

Ontology

An important area in metaphysics is ontology. Some theorists identify it with general metaphysics. Ontology investigates concepts like being, becoming, and reality. It studies the categories of being and asks what exists on the most fundamental level.[124] Another subfield of metaphysics is philosophical cosmology. It is interested in the essence of the world as a whole. It asks questions including whether the universe has a beginning and an end and whether it was created by something else.[125]

Key Topic: Whether Reality Only Consists of Physical Things

A key topic in metaphysics concerns the question of whether reality only consists of physical things like matter and energy. Alternative suggestions are that mental entities (such as souls and experiences) and abstract entities (such as numbers) exist apart from physical things. Another topic in metaphysics concerns the problem of identity. One question is how much an entity can change while still remaining the same entity.[126] According to one view, entities have essential and accidental features. They can change their accidental features but they cease to be the same entity if they lose an essential feature.[127] A central distinction in metaphysics is between particulars and universals. Universals, like the color red, can exist at different locations at the same time. This is not the case for particulars including individual persons or specific objects.[128] Other metaphysical questions are whether the past fully determines the present and what implications this would have for the existence of free will.[129]

Other Major Branches

There are many other subfields of philosophy besides its core branches. Some of the most prominent are aesthetics, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, philosophy of religion, philosophy of science, and political philosophy.[130]

Aesthetics

Aesthetics in the philosophical sense is the field that studies the nature and appreciation of beauty and other aesthetic properties, like the sublime.[131] Although it is often treated together with the philosophy of art, aesthetics is a broader category that encompasses other aspects of experience, such as natural beauty.[132] In a more general sense, aesthetics is "critical reflection on art, culture, and nature".[133] A key question in aesthetics is whether beauty is an objective feature of entities or a subjective aspect of experience.[134] Aesthetic philosophers also investigate the nature of aesthetic experiences and judgments. Further topics include the essence of works of art and the processes involved in creating them.[135]

Philosophy of Language

The philosophy of language studies the nature and function of language. It examines the concepts of meaning, reference, and truth. It aims to answer questions such as how words are related to things and how language affects human thought and understanding. It is closely related to the disciplines of logic and linguistics.[136] The philosophy of language rose to particular prominence in the early 20th century in analytic philosophy due to the works of Frege and Russell. One of its central topics is to understand how sentences get their meaning. There are two broad theoretical camps: those emphasizing the formal truth conditions of sentences[d] and those investigating circumstances that determine when it is suitable to use a sentence, the latter of which is associated with speech act theory.[138]

Philosophy of Mind

The philosophy of mind studies the nature of mental phenomena and how they are related to the physical world.[139] It aims to understand different types of conscious and unconscious mental states, like beliefs, desires, intentions, feelings, sensations, and free will.[140] An influential intuition in the philosophy of mind is that there is a distinction between the inner experience of objects and their existence in the external world. The mind-body problem is the problem of explaining how these two types of thing—mind and matter—are related. The main traditional responses are materialism, which assumes that matter is more fundamental; idealism, which assumes that mind is more fundamental; and dualism, which assumes that mind and matter are distinct types of entities. In contemporary philosophy, another common view is functionalism, which understands mental states in terms of the functional or causal roles they play.[141] The mind-body problem is closely related to the hard problem of consciousness, which asks how the physical brain can produce qualitatively subjective experiences.[142]

Philosophy of Religion

The philosophy of religion investigates the basic concepts, assumptions, and arguments associated with religion. It critically reflects on what religion is, how to define the divine, and whether one or more gods exist. It also includes the discussion of worldviews that reject religious doctrines.[143] Further questions addressed by the philosophy of religion are: "How are we to interpret religious language, if not literally?";[144] "Is divine omniscience compatible with free will?";[145] and, "Are the great variety of world religions in some way compatible in spite of their apparently contradictory theological claims?"[146] It includes topics from nearly all branches of philosophy.[147] It differs from theology since theological debates typically take place within one religious tradition, whereas debates in the philosophy of religion transcend any particular set of theological assumptions.[148]

Philosophy of Science

The philosophy of science examines the fundamental concepts, assumptions, and problems associated with science. It reflects on what science is and how to distinguish it from pseudoscience. It investigates the methods employed by scientists, how their application can result in knowledge, and on what assumptions they are based. It also studies the purpose and implications of science.[149] Some of its questions are "What counts as an adequate explanation?";[150] "Is a scientific law anything more than a description of a regularity?";[151] and "Can some special sciences be explained entirely in the terms of a more general science?"[152] It is a vast field that is commonly divided into the philosophy of the natural sciences and the philosophy of the social sciences, with further subdivisions for each of the individual sciences under these headings. How these branches are related to one another is also a question in the philosophy of science. Many of its philosophical issues overlap with the fields of metaphysics or epistemology.[153]

Political Philosophy

Political philosophy is the philosophical inquiry into the fundamental principles and ideas governing political systems and societies. It examines the basic concepts, assumptions, and arguments in the field of politics. It investigates the nature and purpose of government and compares its different forms.[154] It further asks under what circumstances the use of political power is legitimate, rather than a form of simple violence.[155] In this regard, it is concerned with the distribution of political power, social and material goods, and legal rights.[156] Other topics are justice, liberty, equality, sovereignty, and nationalism.[157] Political philosophy involves a general inquiry into normative matters and differs in this respect from political science, which aims to provide empirical descriptions of actually existing states.[158] Political philosophy is often treated as a subfield of ethics.[159] Influential schools of thought in political philosophy are liberalism, conservativism, socialism, and anarchism.[160]